Storying the Report: A RiverJourney into BIPOC Leadership Energies

BIPOC Leadership Energies (BLE) began as a series of conversations in the Spring of 2021. While we were still in the throes of feeling isolated, the desire to act and be in the world in a better way was present, pressing and calling. Over the phone or over zoom, sometimes in pairs and sometimes in groups, we began to weave together what we experienced with what we wanted. Continue

The B←→I←→POC Leadership Energies (BLE) project is a collaborative research project that created interagency peer mentoring and coaching supports that advance nonprofit Indigenous, Black and racialized leadership. This work involved exploring the ways women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders have been oriented towards leadership while establishing a new orientation marked by empowerment and both self and collective affirmation; key tools to counter cultures of white supremacy that threaten the ability to flourish in leadership.

Storying the Report: A RiverJourney into BIPOC Leadership Energies

BIPOC Leadership Energies (BLE) began as a series of conversations in the Spring of 2021. While we were still in the throes of feeling isolated, the desire to act and be in the world in a better way was present, pressing and calling. Over the phone or over zoom, sometimes in pairs and sometimes in groups, we began to weave together what we experienced with what we wanted.

We didn’t start from scratch. BLE is informed by the many ways in which we were already doing our best to advance untapped, often marginalized, leadership at our respective organizations and sometimes in ourselves. But what really started this journey and what BLE is built from in particular, are the numerous conversations from TNC’s BIPOC Affinity Group over the course of three years that led to the 2019 BIPOC Recommendations, a truly generous labour of love from over a 100 of our colleagues. BLE also drew inspiration from Catholic Crosscultural Services’ Leaders in Training pilot, under Agnes Thomas’ leadership, to develop a more inclusive and effective leadership landscape within their organization.

BLE:

- heeds the call to create networking structures to support the mobility of aspiring BIPOC leaders with ample meaningful pathways and supports

- addresses the glaring gap in BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and nonbinary leadership across organizations and boards in the city despite our overwhelming presence and expertise

- grounds itself in the powerful capacity that already exists amongst us

BLE Report Orientation with Dr. Shah and Ms. Sodhi

We offer deep gratitude to the brilliant Dr. Vidya Shah and Myrtle Henry Sodhi for their insightful facilitation and for creating this report.

We would also like to thank Myrtle Henry Sodhi, integrative artist and facilitator for the breathtaking artwork throughout this written report and on the website.

And thank you to Barry Veerkamp for building us a beautiful home on the web.

BLE came into being from an exercise in reimagination and manifested into this offering. As you dip your feet into this river, please take a moment to offer gratitude to the BLE co-creators whose streams of wisdom and possibilities converge here: Michelle Adams, Nadia Afrin, Rahma Ahmed, Yvette Bailey, Amanda Bland, Jun Emperador, Natasha Francis, Bonnie Hunter, Nermeen Khafagy, Dayanne Martinez, Becky Mcfarlane, Yamikani Msosa, Sree Nallamothu, Vanessa Patterson, Vasanti Persaud, Jaymie Sampa, Ayaan Shire, Chase Tam, Sathya Thillainathan, Agnes Thomas, Jacq Hixon Vulpe, Chanelle Wright and TNC’s BIPOC Affinity Group..

In solidarity.

BLE Community Partners:

BLE Academic Partnership:

Land Acknowledgement

While our sessions were online, participants gathered remotely from various parts of Tkaronto, a Mohawk word meaning “the place in the water where the trees are standing” which is said to refer to the wooden stakes that were used as fishing weirs in the narrows of local river systems by the Haudenosaunee and Huron-Wendat (United Way of Greater Toronto, para. 6) Continue

Land Acknowledgement

While our sessions were online, participants gathered remotely from various parts of Tkaronto, a Mohawk word meaning “the place in the water where the trees are standing” which is said to refer to the wooden stakes that were used as fishing weirs in the narrows of local river systems by the Haudenosaunee and Huron-Wendat (United Way of Greater Toronto, para. 6).

For thousands of years, this land has been cared for by many Indigenous people. We want to acknowledge the Anishnabee, the Huron-Wendat, the Haudenosaunee and the Ojibway and Chippewa peoples in particular. We would also like to acknowledge the Mississaugas of the Credit, the current treaty holders of Treaty 13, The Toronto Purchase. This land is also covered in the Dish with One Spoon Territory, a treaty between the Mississaugas, the Anishnaabe, and the Haudenosaunee that bound them to share and care for the land.

Since colonization, there continues to be gross indignities and inhumane acts of oppression. We acknowledge our national shame of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls across Canada, the environmental degradation of sacred waters and land due to resource development policies, and the need for major public investments in Indigenous education, health care, social services, water infrastructure, and housing to provide even basic access to rights and well-being. We acknowledge the state-sanctioned violence and murder against Indigenous people, our shameful history of residential schools and the many unmarked graves that continue to be uncovered, and the impact the Indian Act has had and continues to have on Indigenous Peoples.

For as long as there has been colonization, there has been resistance to colonization. We would like to acknowledge and pay respect to ongoing acts of Indigenous resistance and resurgence through Indigenous scholarship, art, poetry, social movements, industry, medicine, language revitalization, spirituality, rematriation, and more.

We also recognize the ways in which histories and present-day experiences of multiple colonizations interact with one another and influence our relationships to these lands. Some of us were forcibly brought to these lands through various violent acts. We acknowledge the many people of African descent whose ancestors were forcibly displaced against their will and exploited for labour as part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. They are not settlers. We honour the ancestors of African origin and descent and pay tribute to their innumerable contributions.

Some of us have come to these lands seeking asylum from unsafe conditions caused by colonialism, white supremacy, imperialism, and xenophobia. Some of us arrived on these lands by choice as immigrants over the last several hundred years, and many, more recently as newcomers. We acknowledge that Canada has been and continues to be built on the free, exploited labour of many racialized immigrant and migrant communities through extractive, capitalistic practices and policies.

With the varied complexities in how we have arrived on these lands and varied experiences and histories of colonization, we consider our responsibilities as treaty people to care for all our relations - the lands, waters, human life, and more-than human life. We also consider how our silences and feigned innocence contributes to the ongoing displacement, genocide and forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples, and commit to upholding the 94 Calls to Action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report. We also commit to co-creating different futures and different presents that affirm our collective liberation through truth, solidarity, and love. May our rivers merge into something more beautiful and sustaining than any one river alone.

This land acknowledgement was influenced by:

- The United Way of Greater Toront’s Land acknowledgments: Uncovering an oral history of Tkaronto

- The 519’s Land Acknowledgment: We are all Treaty people

- Dwayne Brown, PhD Candidate, York University, Faculty of Education

Living Into the Tensions

There are three important tensions we want to name at the outset of this report. Continue

Living Into the Tensions

There are three important tensions we want to name at the outset of this report.

First, we want to complicate the term BIPOC, which means Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour. The origins of the term BIPOC were to display solidarity between groups who are impacted, albeit it differently, by intersecting systems of oppression such as white supremacy, settler/colonialism, cisheteropatriarchy, ableism, capitalism, imperialism, and Christian hegemony. However, the term has been co-opted to essentialize differences between and among these groups, frame the global majority as “racial minorities”, and has been made synonymous with non-white (recentering whiteness and white people as the norm). Furthermore, BIPOC does not capture the power asymmetries and the very different histories between and within these groups, making efforts at solidarity much more complicated and complex, which TNC commits to make space to address in our continued work together. In this report, we will make reference to B←→I←→POC, speaking to the differences and the relations between these groups, while recognizing that this, too, is also an incomplete representation. You may also see us making reference to Black, Indigenous, and racialized people throughout the report as intentional notation to remember these important differences.

Second, we want to complicate our references to gender and sexual diversity. This group was open to people who identify as B←→I←→POC, but also to people who identify as women, 2-Spirit, trans, and non-binary folks. While we name these identities throughout the report, we do not actually know if there is representation from each of these identities. Furthermore, we hesitate in this naming because we also do not want to collapse and group all identities that are not man, essentially centering men again. A limitation of this report is that it does not speak to the specific ways in which leadership operates in and through each of these identities separately and specifically and runs the risk of over-generalizing the findings. We invite you to read the report with this limitation in mind, and further, expand and extend it to address our shortcomings.

Third, we want to complicate our role as researchers and facilitators in this process. We have gone back and forth between using us/we and them/they as we share experiences and findings. “Us/we” recognizes relation and recognizes that we, a Brown woman and a Black woman, find and affirm ourselves in the words in this report. This is our experience, too. “Them/they” acknowledges the important separation that is needed between those who experience the project and those who both experience and analyze the project and research findings. In this in-between space, we have ethical and intellectual obligations to create important boundaries (Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2019). We graciously accepted the invitation by the group to use “us/we” and to join in the experience, while holding these tensions close to our hearts and minds.

We invite you to journey with us down these rivers.

Orientations

An Embodied Approach to Healing on our Leadership Journey We recognize the importance of an embodied approach to countering cultures of white supremacy in our leadership journeys. Recognizing the importance and integration of our bodies, minds and spirits, we embraced an integrative approach to honouring our leadership lineages, healing our leadership wounds, and imagining leadership possibilities. This embodied approach counters the orientation of disconnection and the practice of fragmenting the self, which are logics of the culture of white supremacy. Separating the mind from the body and the spirit, and separating humans from one another and the more-than-human world provides us a blueprint for dispossession, dehumanization, and destruction. Continue

Orientations

An Embodied Approach to Healing on our Leadership Journey

We recognize the importance of an embodied approach to countering cultures of white supremacy in our leadership journeys. Recognizing the importance and integration of our bodies, minds and spirits, we embraced an integrative approach to honouring our leadership lineages, healing our leadership wounds, and imagining leadership possibilities. This embodied approach counters the orientation of disconnection and the practice of fragmenting the self, which are logics of the culture of white supremacy. Separating the mind from the body and the spirit, and separating humans from one another and the more-than-human world provides us a blueprint for dispossession, dehumanization, and destruction. For example, bodies are used for labour in ways that continue to be exploitative and limiting because the mind and the spirit have been both separated and neglected. Through practices that acknowledge both our lived experiences and our dreams, we were able to embrace an approach that affirms and centres the integration of body, mind, and spirit, developing in us the ability to dream new leadership worlds for ourselves and others. An embodied approach to exploring our leadership journeys involves:

- Understanding the body as a site of both harm and liberation.

- Honouring relations over transactions. In this approach relationships are recognized as complex and dynamic, with the potential for ease and conflict.

- Tuning into our abilities and wisdoms as responses and tools to confront white supremacy culture.

- Embracing the bi-directionality of individual expressions of leadership within larger communities and influences of the larger communities on individuals.

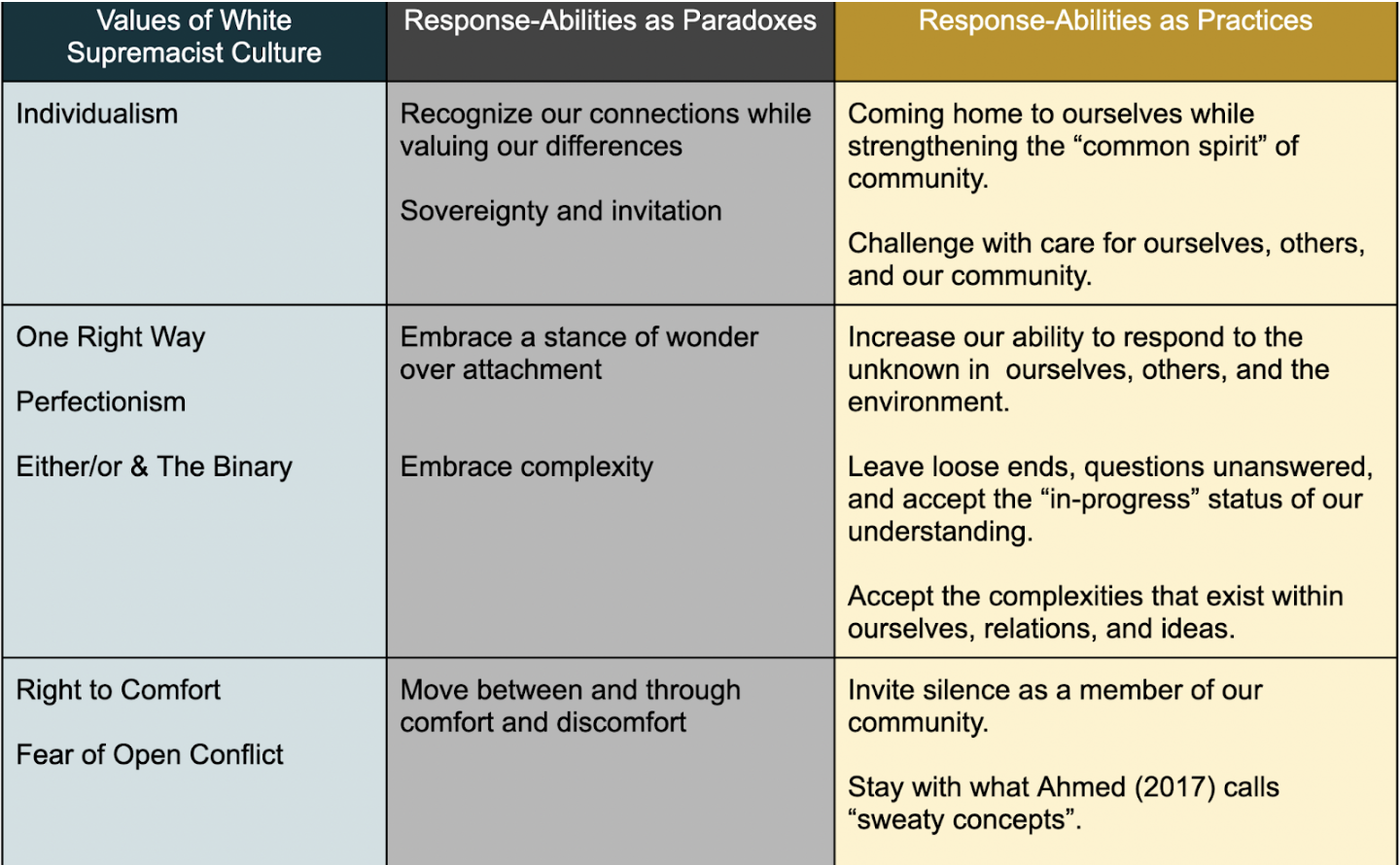

Response-Abilities in Countering White Supremacist Culture

Response-Abilities highlight practices that support responding to ourselves, others, and the environment. When confronted with the culture of white supremacy, we are often left feeling disempowered. Cultivating a mindset that strengthens our ability to respond empowers us to restore relations and acknowledge our needs, bringing us back home to ourselves and our communities. A response-ability mindset neither expects nor adheres to false notions of “perfection”; rather, it invites us into the ongoing processes of learning, being, and becoming.

Response-abilities* invite us to:

- Embrace courage and wisdom to recognize our connection and value our difference

- Develop abilities to move between zones of comfort and discomfort, recognizing the many Black, Indigenous, and racialized people rarely experience and rest in comfort

- Recognize and understanding how our unique and dynamic identities are influenced and shaped by the larger community, and vice versa

- Challenge others while attending to well-being. This involves navigating commitments, words, and actions with confidentiality, safety, and care

Below we share an approach to response-abilities as practices:

Paradoxes & Complexities

One of our central response-abilities is to counter cultures of white supremacy. In doing so, we orient ourselves and our work in a way that calls us to not only identify its characteristics but also develop an awareness of the paradoxes that a response presents. Embracing complexity and a stance of wonder over attachment to preconceived notions or our particular truths increases our ability to respond to the unknown within ourselves and others. Allowing questions to linger and remain unanswered and not only accepting, but expecting our thinking to be unfinished, encourages an approach of progress over product.

White supremacy culture often demands "one right way" of thinking, which is reflective of the characteristics of perfection and binary thinking it clings to. In prioritizing complexity and multiple ways of knowing as response-abilities, we were able to create spaces to practice countering the harms experienced as a result of white supremacy culture, and allow ourselves to dream different futures for ourselves and others. The concept of “staying with sweaty concepts" (Ahmed, 2017) resists the tendency to be conflict-avoidant and notions of the right to comfort. As Sara Ahmed (2017) explains:

“A sweaty concept is one that comes out of a description of a body that is not at home in the world…A sweaty concept might come out of a bodily experience that is trying. The task is to stay with the difficulty, to keep exploring and exposing this difficulty…Not eliminating the effort or labor becomes an...aim because we have been taught...not to reveal the struggle we have in getting somewhere” (Ahmed, 2017, p. 13).

Response-abilities are about developing a counter response to the violence we experience in the workplace that supports cultures of white supremacy.

Throughout the sessions, we embraced paradox and complexity as critical orientations to enact liberated leadership approaches. Recognizing that our work together will involve an acceptance of paradox deepened our understanding of the complexities that exist within our work, within ourselves and with each other, and with the systems that create barriers to our liberatory leadership journeys, narratives, and connections.

De-centering the Power of One

In order to continue to counter the ways of knowing and being that create obstacles in the leadership journeys of BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary folks, we addressed the harm that is done through centering the power of one. In speaking to the power of one we are resisting a system and worldview that assumes the supremacy of one knowledge system, one leader, one ‘right way’, and one generation/time. We recognize that our power and our effectiveness is achieved through an embrace that includes the awareness and acceptance of dynamic knowledge systems that are built on multiple knowledges, leadership styles, and collectives of people, ideas, and the more-than-human. There is power in the multitude, and we draw on this power to anchor our conceptions of leadership.

Inner-Outer Fractal Leadership:

How we are at the small scale is how we are at the large scale. The patterns of the universe repeat at scale. There is a structural echo that suggests two things: one, that there are shapes and patterns fundamental to our universe, and two, that what we practice at a small scale can reverberate to the largest scale. —adrienne maree brown in Emergent Strategy (2017, p. 54).

adrienne marie brown speaks of emergent strategies found in nature that can become inspiration for leadership practices. One such example is the fractal strategy. The fractal strategy speaks to the value of connection in terms of what happens on the larger scale is a mirror to what happens on smaller scales. Therefore, honouring our familial, ancestral, and communal ways of knowing in our most private and intimate moments ripples into our relations, ideas, institutions, and environments. The same stands true when we honour cultures of white supremacy in our most private and intimate moments.

Telling the Story

Session 1 - Re-Memorying: Sitting at the Feet of Our Stories Session 2 - How We are Storied Session 3 - (Re)Storying Ourselves: Connecting Backward to Connect Forward Continue

Telling the Story

Session 1 - Re-Memorying: Sitting at the Feet of Our Stories

De-colonial scholar Toyin Falola (2022) explains that "memory narratives have become a liberating tool, allowing individuals to think beyond restrictions imposed by various intuitions. For the narrator and the reader, it provides multiple facts to renegotiate existing knowledge" (p. 80). One of our early tasks in our first gathering was to employ "rememory" practices that supported our understanding of our leadership experiences. We mapped out our leadership journeys. We remembered some of the ways we have been storied as leaders, speaking to the stories that have been told about us through representations, misrepresentations, or complete lack of representation. These narratives were not always in alignment with the diverse truths we hold about leadership. We also recalled and shared ways we take on leadership roles without compensation or recognition in our lives. This practice continued with identifying our missed leadership opportunities, failures, and challenges. We left this activity with a final task where we recognized, named, and honoured the supports that have accompanied us on our various leadership journeys. Through these exercises, we created a "rememory" practice where we revisited a story filled with imposed ideas of leadership, and we were left to reimagine ourselves ready and equipped to renegotiate these knowledges.

Session 2 - How We are Storied

In our second gathering, we began by deconstructing a concept that connected us all. To quote Alexis Pauline Gumbs, "I wonder why...we sometimes name identities and even whole organizations based on our scars.” We begin as if to start from the place that named us. In part, we deconstructed to reveal the contradictions that frame radically different identities, that when grouped together, are reduced to an acronym that erases specificities and power asymmetries. We acknowledged that at times, our identities were acquired, and at other times, they were negotiated. We recognized the spaces that exist between the B←→I←→POC. When we pull the letters apart, we make room for the complexities that exist within our simultaneously shared and separate experiences. We recognized and celebrated the relations that fill the spaces and welcome the common spirit of community that embraces and holds them. We also recognized our intersectional identities of race, gender (expression and identity), sexuality, ability, faith and spiritual worldview, social class, place of birth, accents, diasporic experiences, and more.

Session 3 - (Re)Storying Ourselves: Connecting Backward to Connect Forward

Being aware of the ways we are kept small allows us to analyze how those ideas influence both what we dream of, and what we practice. In our third session, we also became aware of what liberation may or may not look like and feel like, alongside how access to liberatory leadership changes considering elements such as time, space, context, and history. Recognizing the policies, practices, structures, and community relations that shape our lived experiences and ultimately our dreams of leadership, involves ongoing practices of "rememory".

Conflicts, Harm & Apologies

Throughout our sessions, we encountered struggles that made us aware of how we have been conditioned to see and handle conflict through a lens supported by white supremacy culture. To (re)story our leadership journeys we understood the importance of responsibility and relationality in addressing conflict and harm, and positioned conflicts as opportunities for generativity and wisdom-sharing. Continue

Conflicts, Harm & Apologies

Throughout our sessions, we encountered struggles that made us aware of how we have been conditioned to see and handle conflict through a lens supported by white supremacy culture. To (re)story our leadership journeys we understood the importance of responsibility and relationality in addressing conflict and harm, and positioned conflicts as opportunities for generativity and wisdom-sharing.

Working Through Conflict

Conflict and harm are inevitable in all spaces given differences in power and intersectional identities. Through this process, we were encouraged to accept conflict as a naturally occurring element of transformative work. Rather than ignore conflict, we found ways to acknowledge and learn from it. This approach was centered on co-creating knowledge, deepening love for ourselves and one another, and developing an appreciation and celebration of the complexity within diversity. This approach challenges fantasies of safety and comfort in racial affinity spaces and challenges a tendency to romanticize the leadership and leadership experiences of Indigenous, Black and racialized people.

In idealizing the leadership of Indigenous, Black and racialized women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders, we not only set them up for failure, but we also perpetuate characteristics of white supremacy culture such as perfection, product of process, and “one right way”. What if we viewed leadership as opportunities for struggle and resistance, where we are collectively making and remaking what it means to be in relation to one another and in service to justice, humanity, and care? In doing so, we might accept a version of love and care that necessitates conflict. bell hooks famously explained in a (2002) interview: "When people love people, they never think they are going to think the same...Why do we expect that we’re going to get together and talk about race and racism and not have, perhaps, anger or conflict... We recognize conflict is about trying to have a relationship with someone who is not you" (Forum, 2016).

Addressing the Harm

In centering response-abilities, we can enter conversations with more nuance around conflict, harm, safety, and love. BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary folks when working together are not immune to conflict, and we must acknowledge that the idealization of this group creates opportunities for harm. During the sessions we identified denial as a key practice that supports the refutation of systemic racism. We were challenged with the question of whether we will face conflict directly or continue with practices of denial. We agreed to move forward with an unwillingness to be in denial. In that way, we accept that our approach is concerned with a response to conflict rather than the fear, denial, or delusion of its presence.

The Apology

In accepting that conflict is a part of our leadership journey we acknowledged that redress is an essential part of the conversation. Drawing from Rania El Mugammaar's Anatomy of an Apology we embraced the multifaceted nature of an apology, which includes consent, acknowledgement, emotional uptake, centering the hurt, accountability, changed behaviour, and divesting from forgiveness. This exploration of an apology provides a more meaningful way of engaging with conflict as BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders. We are supported in drawing towards the hurt and harm, rather than retreating to an attachment to innocence through denial. We are invited to see ourselves as Prentis Hemphill describes as “harmed and harming” and recognize our complicity rather than seek immediate "solutions" to absolve ourselves of responsibility, which only replicates structures and logics of white supremacy.

Themes

During the Leadership Energies Project we uncovered three themes that emerged through the focus groups and individual surveys. These themes include:

- Complicated Relationships to Leadership

- The Colour of Extractive Labour

- Leadership as Liberation

Throughout our discussions a common challenge emerged, wherein participants expressed discomfort in embracing the word “leadership”. BLE participants expressed ambivalence towards the word. It emerged that this rejection is partly due to the close associations between leadership and practices of power that are closely associated with harm, misuse, and dominance.

ContinueThemes

During the Leadership Energies Project we uncovered three themes that emerged through the focus groups and individual surveys. These themes include:

- Complicated Relationships to Leadership

- The Colour of Extractive Labour

- Leadership as Liberation

Throughout our discussions a common challenge emerged, wherein participants expressed discomfort in embracing the word “leadership”. BLE participants expressed ambivalence towards the word. It emerged that this rejection is partly due to the close associations between leadership and practices of power that are closely associated with harm, misuse, and dominance.

How we Came to These Ideas

As “insider-outsider researchers” (Minh-ha, 1988) who identify in both similar and different ways with the participants we acknowledge the complexities our role presents. We acknowledge that the members of TNC are the central voice throughout the process while also being cognizant of the presence of our own voices. As Brown and Black researchers who identify as women, we acknowledge this “insider-outsider” position and accept the privilege of not only walking with the TNC community but also being aware of the responsibility our presence requires. Black feminist approaches to research operationalizes the in-between/third-space positionality of the researcher as a space that acknowledges the relational and differing identities and positionalities that are represented when working with affinity groups (Patterson et. al., 2016, Minh-ha, 1988). Decolonial and other emancipatory research methodologies center relationship and the positionality of the researcher as important to any research project that aims to be of service to the community (Collins, 2022; Falola, 2022; Patel, 2016). Leigh Patel (2016) explains that it is important to acknowledge that research is situated with the relational because this awareness creates the conditions for research that will be a vehicle for creating change that is liberatory in nature. With this in mind we recognize that the report should reflect this relational process and orientation. This is the place we not only start with but it is the path we continue to walk with the TNC community throughout this report. At times the report will include our voices alongside those of the TNC community– an intentional way of acknowledging the relational. At the same time we recognize that the voice of the TNC community is the main voice this report speaks with. We will use “we”, “us”, to show the places we have walked together as subjects and will use “their”, “them” and such for places where the community members are directing the process and the path. The intentional use of this type of language in the report will reflect the relational aspect embedded in the project.

Theme 1: Complicated Relationships to Leadership

- “We’re all equals – I can learn from you, and you can learn from me. What separates us is a title.”

- “You are not doing it for recognition but just what you would like to do.”

- “Sometimes you do your best to get to that bar of leadership and then the bar gets pushed up further.”

Theme 1: Complicated Relationships to Leadership

- “We’re all equals – I can learn from you, and you can learn from me. What separates us is a title.”

- “You are not doing it for recognition but just what you would like to do.”

- “Sometimes you do your best to get to that bar of leadership and then the bar gets pushed up further.”

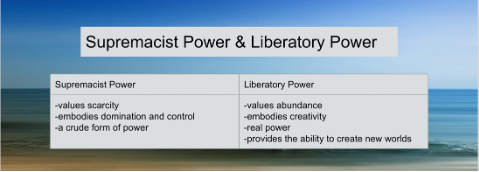

Cultivating a “Powerful Identity”: BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary communities have complicated relationships with power because power is often used against them to further their oppression. How our communities identify with power relates to their experiences with dominance. When asked to share their first examples of leadership, participants spoke about leadership from two vantage points. Definitions of formal leadership included people in political or social roles who are driven by power and position. Participants questioned the effectiveness of this type of leadership for social advancement, community well-being, and equity. Informal leadership models were often inspired by leaders in families and communities. Informal leaders were described as visionaries, people driven by amplifying the voices of others over their own. Informal leaders are concerned with progress and growth for the community, and therefore have strong abilities to share power and collaborate with others. Matriarchal approaches to leadership figured strongly here. Therefore, formal leaders desire to garner power over others and informal leaders are motivated by family and community growth and power sharing. While this characterization appears to dichotomize leadership into formal and informal leadership roles, participants noted complexities and areas of overlap. For example, some participants recognized that familial and community roles can involve instances where power is misused.

An experience where dominance is accepted as the norm creates an identity where people of colour see themselves as powerless whereas an experience where dominance is rejected creates an identity that is connected to a feeling of being powerful (Suarez, 2018). Cultivating a “powerful identity” means that leaders embody power as a liberating practice.

Participants expressed the importance of learning about the differences between supremacist and liberatory power. Suarez (2018) explains that supremacist power transmits power whereas liberatory power transmutes power. It is this ability to transform that makes liberatory power so important for re-envisioning leadership. The ability to transform is about new world building. The ability to not only access power but also to make it possible for others to have similar access is essential to the success of BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders. Committing to liberatory power requires that supremacist power is disrupted. This is the only way leaders can change their relationship to power and organizations that they work within.

source: Cyndi Suarez

Re-orienting power requires examining values and responding to these values in ways that are counter to cultures of white supremacy. Response-abilities our initiations to countercultures to white supremacy.

| Values of White Supremacist Culture | Response-Abilites Practices |

|---|---|

| Individualism |

Coming home to ourselves while strengthening the "common spirit" of community. Challenge with care for ourselves, others, and our community. |

|

One Right Way Perfectionism Either/or & The Binary |

Increase our ability to respond the unknown in ourselves. others, and the environment. Leave loose ends, questions unanswered, and accept the "in-progress" status of our understanding Accept the complexities that exist within ourselves, relations, and Ideas |

|

Right to Comfort & Fear of Open Conflict |

Invite silence as a member of our community. Resist the urge to claim innocence. Stay with what Ahmed (2017) calls "sweaty concepts". Accept the complexities that exist within ourselves, relations, and ideas. |

|

Progress is Bigger/More and Quantity over Quality |

Focus on impact on the community |

Values, whether they promote white supremacy or response-abilities are embedded in organizations and institutions and thus instruct the way power is experienced and accessed.

Limits to a Politics of Representation: Participants remarked that representation was an area of struggle for two reasons. First, there is a lack of representation of leaders from gender equity deserving groups. Second, when people are in leadership positions, they are often the token hire in organizations to tick the “diversity” checkbox. A focus on increased representation, outside of an analysis of power, results in harmful conditions for staff (Shah et al., 2022b). For example, participants shared that are simultaneously romanticized and held on a pedestal while being severely limited in how and to what degree they can express their humanity. leaders often experience challenging relationships to power in which their leadership is characterized less as having access to power and more as being burdened with stereotypes and saddled with heavy workloads.

Experiencing Racism Across the Fractals: Participants shared many examples of experiences racism across the fractals, including internalized oppression at the individual level, regular microaggressions from white colleagues at the interpersonal level, hidden expectations of additional labour at the cultural level, unfair pay structures and unpaid labour at the institutional level, and essentializing the experience of all staff at the ideological level, as though all of their experiences are the same. Below is a chart from Turner Consulting Group (2015) that illustrates the fluidity of racism across multiple spheres or fractals, which all have professional and personal impacts on Indigenous women, Black women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders. Theorizing racism across spheres or fractals helps leaders demand and create change for themselves and the organization.

Ecological Racism: The ecological realm speaks to the larger socio-political, economic and environmental context of white supremacy in which organizations operate. Participants spoke to the ways in which organizations are indirectly punished by funding agencies, media, etc. for appearing “too radical” or “too controversial” in their programming, focus, and activism. Furthermore, according to the Trading Glass Ceilings for Glass Cliffs (2019) report, organizations that are led by Black, Indigenous, and racialized leaders are often underfunded. This creates inequitable and burdensome challenges for leaders. Leaders willing to disrupt white supremacy view their role as influencing public discourse, influencing the focus and accountability of philanthropic agencies, and influencing various levels of government and policymakers whose decisions impact the communities they serve.

Re-orienting Power: How Does Power Operate in Re-envisioning Leadership?

- Leadership is “Not hovering and dictating – you’re leading by example”

- Leadership is “Collaboration – [there is] not much difference between a manager and director vs. someone who isn’t, other than the title. There is experience and knowledge that comes with those titles, so you can direct energy of different folks to meet a common goal”

- When someone “makes it” – ppl are almost leading the way for the next wave – giving advice, checking in, (like parents and siblings – throughline into the workforce)

- “(A) leader is not someone who always shows off their power (makes all decisions).”

Theme 2: Colour of Extracted Labour

- “I have to work myself to the ground to prove myself.”

- “I have to justify why I need rest, so I can be more productive.”

- “After 2 years, the shininess goes, and you feel underappreciated and overworked.”

Theme 2: Colour of Extracted Labour

- “I have to work myself to the ground to prove myself.”

- “I have to justify why I need rest, so I can be more productive.”

- “After 2 years, the shininess goes, and you feel underappreciated and overworked.”

For Indigenous women, Black women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders to thrive in their roles, it is important to consider that current orientations to power have been based on exploitative practices.

Problematizing Validation

Several participants named that feelings of validation did not come from leaders or upper management; feelings of validation have come from the gratitude of service-users, youth, and community members. Some participants shared that validation is predicated on their ability to conform to whiteness (e.g., don’t question the system or those with more power, work at unsustainable rates, protect those in power even if they have behaved unethically, etc.). Other participants identified a pattern that Black, Indigenous, and racialized staff are invited in as “collaborators” and their ideas, energies, and creativity are mined for the organization, but little/no action is taken to honour their ideas for transformative change. This leads to growing mistrust and disengagement of Black, Indigenous, and racialized staff.

Consultation without transformative action and “increasing voice” without challenging power structures are not examples of validation or inclusion. They are examples of extraction and whiteness.

Participants spoke to the pattern of senior leaders and management valuing “outsiders” or “outside experts” more than internal staff who may already be doing the work. As a result, staff from within an organization may leave because they are more valued as “outsiders” in another space, which increases their opportunities for upward mobility and growth. Furthermore, training and orienting new folks becomes the responsibility of folks within the organization, often folks, without the acknowledgment of additional labour.

Not validating the work of staff, validating them only for their “racial” contributions, or devaluing their contributions while expecting them to “do the work” can lead to staff experiencing imposter syndrome and questioning their worth. As one participant shared, “I have to demand that I am valued”.

Unfair and Changing Labour Expectations

Participants shared that women, 2 Spirit, trans and gender non-binary staff and leaders are expected to work harder and faster than white colleagues with less formal recognition, compensation, and support. This means harmful assumptions are made that staff can carry heavier workloads, which often means they have multiple jobs at once. For example, leaders are tasked with supporting other leaders with less experience, while receiving very little support themselves from their white colleagues and leaders. They are often tasked with restoring justice and/or providing emotional support after harm has been done by others or the organization. If women, 2 Spirit, trans and gender non-binary staff question the heavier workload, they are seen as incapable, their “fit” is questioned, their commitment is questioned, and they are advised to better manage their time. However, if their work and output outshine someone in a position of formal or informal power, they are then silenced and shut down.

Participants also shared that overworking is the hidden expectation in order to “move up” in an organization. This is sustained by positioning increased work as a compliment. “You’re so fast! You’re amazing at your job!” This is not validation; it is extraction. Instead of complimenting how much work staff are doing, staff would better be served by taking extra work off their plates and changing the toxic culture of urgency. It is also sustained by moving work and leading from the formal to informal realms, such as informal mentoring relationships, logistical work, the work to maintain and strengthen relations and improve organizational culture, most of which are unaccounted for in pay or time returned. For example, attending workshops/affinity spaces as part of work should happen during paid work hours, not during the personal time or on the personal dime of staff.

Participants spoke to unfair and changing labour expectations that are sustained when we position work as “family”. Positioning working relationships as “family relations” often blurs boundaries and expectations because you can ask more of a family member than you can of a co-worker. This association often leads to extractive orientations that disproportionately harm folks whose belonging is predicated on increased labour. This makes it harder for staff to ask for support, growth opportunities, more pay, etc. Therefore, while building strong, respectful, and trusting relationships is central to any work environment, labour expectations need to be distinct from approaches to relationship-building.

Finally, participants described how the unfair labour expectations result in discriminatory pay structures. There is a major discrepancy in pay between formal leaders and staff in an organization. Some participants shared that a more transparent and fair pay structure is needed. For example, if a project is successful, project leaders should be given more responsibilities and pay. Other participants questioned why pay grows for managers and stays the same for frontline staff. They also questioned why some staff receive health and dental benefits and others do not. What does that say about whose health and well-being matter?

How Leaders Can Challenge Patterns of Extractive Labour

- Encourage all staff to set boundaries and both model and respect their boundaries and your own. Often, those who set and stick to their boundaries are seen as hostile, unprofessional, incapable, and/or uncaring, which promotes unsustainable work environments, patterns of extraction, and a lack of individual and organizational wellness. Challenge these assumptions in yourself and others.

- Make it a habit to identify labour that is hidden, unpaid, and unacknowledged and rework responsibilities to ensure a fair distribution of work. You can also frequently check in with staff about workload expectations and deliverables, acknowledging that everyone’s time is valuable. This may also require pushing back against the expectations of funding agencies and challenging them to distribute their funds more justly.

- Humanize the experience of all staff. Provide genuine support and understanding during times of personal challenge and/or global issues that affect us all.

- Increase developmental opportunities for upward mobility within an organization and ensure pathways for upward mobility are clear and transparent. Greater priority needs to be placed on developing structures that grow people within an agency and compensate them accordingly for this growth and development. Pathways can also be created for service users to become service-providers and service-leaders, in which service-users are consulted and should be paid as consultants. These pathways to leadership are investments in community.

- Performance reviews and hiring/promotion metrics should reflect differential needs for white and staff and should prioritize anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-oppression leadership capacities and orientations (Shah et al., 2022; Shah et al., 2023)

- An orientation to vocation needs to be fostered and separated from orientations to labour or climbing the hierarchical ladder. This involves creating opportunities for people to remember and grow in their vocational inclinations and desires.

Theme 3: Leadership as Liberation

- “We are trying to move a building by pushing the wall from the inside.”

- “I can feel my leadership instincts being muted because I don’t have time.”

- “We are rehearsing for the revolution.”

- “I can’t guide the ship if I am broken.”

Theme 3: Leadership as Liberation

- “We are trying to move a building by pushing the wall from the inside.”

- “I can feel my leadership instincts being muted because I don’t have time.”

- “We are rehearsing for the revolution.”

- “I can’t guide the ship if I am broken.”

“Marginality is much more than a site of deprivation … it is also the site of radical possibility, a space of resistance. This marginality offers a central location for the production of counter-hegemonic discourse that is not just found in works but in habits of being and the way one lives. [This is not] a marginality that one wishes to lose-–to give up or surrender as part of moving to the center–-but rather a site one stays in … [The margin] offers to one the possibility of radical perspective from which to see and create, to imagine alternatives, new worlds” (hooks, 1989, p. 341).

The Power of Co: Intentionally Create Space and Time for Co-Dreaming, Co-Visioning, Co-Creating

Co-spaces are affinity spaces for Black, Indigenous, women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary racialized leaders to be in the practice of both undoing harmful approaches to leadership that we are socialized into and imagining something different. These are spaces of imagining, dreaming, visioning, and creating in community, with a collective of people, ideas and experiences merging together and moving apart in response to collective needs, aspirations, and realities. These spaces allow staff to embody approaches to leadership that de/uncolonize the mind and the body as everyday practices.

Co-spaces invite the practice of:

- Power sharing in which power regularly changes hands and roles. For example, mentorship is seen as co-directional, recognizing that we each have experiences and ideas to offer, and we each have areas of growth and expansion

- Being witnessed and witnessing each other in which unheard voices, feelings, and ideas take center stage. We listen to each other’s stories, see ourselves in each other, and create new stories together. There is an invitation to prioritize ourselves and our needs and practice attending to those needs in ways that bring us back home to ourselves.

- Reimaging time and slowing down, to offer increased space for reflection, pause, rest, getting lost, listening to ourselves and one another, making visible our invisible selves as individuals and as collectives, and acknowledging and nurturing our strengths. It is also an invitation to prioritize play, joy, laughter, and rest as an end goal, and not as a means to increase productivity.

- Being good ancestors, in which there is a commitment to creating different realities for future generations of Black, Indigenous, and racialized leaders, and for white leaders.

- Being in joy squared, in which joy is not perceived as a scarce commodity in an environment of competition and individualism, but as compounding and exponential experience in an environment of collaboration. In this way, individual affirmation and celebration becomes collective affirmation and celebration, and the expansion and liberation of each individual becomes the expansion and liberation of all. In other words, the collective experience of joy is greater than the sum of the joy of each individual. As one participant shared, “Your joy is my joy.” Being in joy squared also invites the capacity to hold more comfort and joy in our bodies

- Committing to the practice of solidarity, which involves the acknowledgment that affinity spaces are not free from harm and violence. Even as women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary folks work towards anti-oppression, they will continue to uphold oppression. Oppression may occur in terms of ethno-racial diversity, but may also include gender and sexual diversity, ethno-racial differences, orientations in faith and worldview, experiences of multiple colonialisms, disabilities and different abilities, differences in social class, differences in accents and dialects, differences in experiences of migration and movement, and the relational differences and connections within and between Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities. Committing to the practice of solidarity is the continuous commitment to look to the margins as sites of resistance, radical possibility, and imagination (hooks, 1989).

- Being sites of resistance in which we are living in and practicing for revolutions of care, love, and justice. Resistance and revolution are constructed here as the ultimate acts of deepening interconnectedness between humans and between human and more-than-human life.

- Being more fully human in which we might experience more of the full range of human existence including anger, rage, grief, excitement, mystery, sacredness, fear, insecurity, loss, longing, and desire. It is an acknowledgment that we may be both wounded and healers, both harmed and harming (Hemphill, n.d.), both flawed and forgiven/redeemable, both imperfect and perfect, both learners and teachers.

- Committing to liberatory practices of integration is marked by actions that support integration of the self and a focus on reconnecting, reclamation, re-engaging, and restoring what cultures of dominance have distanced, distorted, disconnected, and dissociated us from (Leadership Learning Community). Liberatory practices are about new world building. They are transformational practices that return people to themselves, their communities and their purpose. Below is a graphic from Monica Dennis of Move to End Violence as part of the Liberatory Leadership Webinar Series.

- Engage in a theorizing practice. Black, Indigenous and racialized communities can critique their experiences as leaders and curate counter-practices. As bell hooks explains, the ability to theorize our experiences can be a liberatory practice. She sees theory as an antidote for harmful experiences. hooks explains, “I came to theory because I was hurting...I came to theory desperate, wanting to comprehend—to grasp what was happening around and within me...I saw in theory then a location for healing” (hooks, 1994, p. 59). In the same way, leaders are invited into theorizing practices by deep diving inward and together to gain insight into what was “happening around and within”. Theory involves practices of thinking, examining and critiquing—all of which are essential for leadership to take on a liberatory bend.

- Be in the praxis of leadership in which praxis is the continual interplay between reflecting, theorizing, and developing a critical consciousness on the one hand, and taking action for social transformation on the other. This process asks for a departure from an attachment to knowability in terms of a rigid set of outcomes. Indigenous, Black and radicalized leaders benefit from engaging in critique about their leadership journeys and working to change those conditions as a liberatory and often revolutionary practice.

A cautionary note: We are conditioned into hierarchy, competition, power over, and individualism as models of leadership that uphold systems of power. These conditionings may seep into co-spaces that are attempting to lead differently. These spaces may also fall into the performativity trap, engaging in these practices to check an item, to make an organization appear committed to anti-racism, or to absolve white folks from engaging in the work of anti-racism, anti-colonialism, and anti-oppression as individuals and in the organization.

Co-spaces require dedicated space and time within the course of the workday/workweek in which competing demands to attend to the needs of service-users or complete tasks are limited to the greatest extent possible.

Leadership is a process of re-orienting, re-envisioning, and returning.

The chart below identifies harmful contexts and impacts of white supremacy culture in organizations that need to be dismantled and addressed as well as suggests the systemic change required to redress harm of these contexts and impacts.

| Contexts and Impacts of White Supremacy Culture in Organizations | Systemic Change Required to Redress Harm |

|---|---|

|

Emotional Burdens of Leadership marked by anger, exhaustion, being “stuck”, pain, isolation, and more. |

Recognize the heighted experience of negative emotions for leaders and that emotions are political. Center complex models of leadership for all leaders that can hold both pain and joy, both struggle and ease. This way, white leaders can also share in the experiences of anger and resistance (instead of demonizing these emotions), while working to challenge conditions that lead to exhaustion, being “stuck”, pain, isolation, and more. Challenge structures, practices, and cultures that lead to increased workloads, minimal opportunities for growth and advancement, and unaddressed incidents of racism for staff and leaders. Structures also need to be challenged that protect those who are upholding white supremacy through upholding the status quo or punish those who challenge white supremacy through challenging the status quo. |

|

Work and Leadership as Places of Harm |

A place where creating safety is foundational and aspirational A place where recognition, care, and support are offered |

|

Leadership that Operates on Values of White Supremacy and Colonialism |

Values that stress reflexivity, accountability, interconnectedness, and relationship |

|

Static Nature of Leadership Models |

An orientation where leadership is accepted as a path that evolves alongside people, ideas, and collectives |

|

Leadership Structures Informed by One Knowledge System |

Centering silenced and marginalized ways of knowing and leading, including community-based, Indigenous, countercultural, futuristic, and ecological orientations |

As the River Flows

As the four sessions came to an end, we knew that the water that had passed through our river, at that moment in time, was being regenerated as it took on different forms and pathways. In this section, we will highlight the following pathways: Continue

As the River Flows

As the four sessions came to an end, we knew that the water that had passed through our river, at that moment in time, was being regenerated as it took on different forms and pathways. In this section, we will highlight the following pathways:

- How members of the BLE group have continued and extended the learning with other staff

- Tensions and challenges that may arise that were not named in the data or 4 sessions

- Possibilities and cautions of the replicability and sustainability of this work

- The importance of dreaming different rivers and acknowledging rivers that have always been there

- Resources

Extending the Learning

Members of the BLE Group have been in ongoing dialogue with one another and with TNC about facilitated learning engagements they are planning based on ideas we brainstormed collectively. Each workshop has a different purpose and flavour that acknowledges and affirms the facilitators’ expertise and experiences as well as the needs and interests of Indigenous, Black, and racialized women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders at every level of the organization. We might call this a hybrid space or a liminal space, in which participants are playing with ideas and themes, making sense of the ideas in their own contexts, and transitions from participants to co-facilitators. Below is a list of the workshops offered:

| Workshops | Areas of Focus |

|---|---|

| Self-Care, Inner Journeys |

|

| BIPOC Mentorship, Community Building, Networking, Coaching, Affinity Spaces |

|

| Interdependence |

|

| Re/Imagining & Re/Discovering/ Recapturing/ Relearning/ Reawakening/ Recover/ Regain Leadership |

|

| Imposter Syndrome |

|

Member organizations with participants in the BLE Group have also committed to:

- supporting the participants in growing their leadership

- supporting Black, Indigenous, and racialized staff in the organization

- challenging the ways in which supremacy, settler colonialism, cisheteropatriarchy, and other systems of oppression operate structurally in their leadership practices.

North York Community House - Bonnie Hunter

The BLE project is invaluable in deepening NYCH’s ability, and my own ability as a CIS white woman and leader, to identify and challenge systemic oppression within our organization, and to create intentional, meaningful affinity spaces and leadership pathways for Indigenous women, Black women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders. The BLE project surfaces stories, strengths, traumas, learnings and celebrations that confront the complexities of ‘leadership’ as I was raised to define it, in the context of reifying white supremacist and colonial ideologies. It provides tools for action and reflection that I can share, and use to remain accountable for the commitments I’ve made to doing the hard work of changing the systems I benefit from, and centering more just and complex models of leadership.

The 519 - Jaymie Sampa

“The BLE project has launched a great opportunity for connection and sharing experiences and learnings across our teams. It is exciting to know it has catalyzed the ongoing creation of spaces for BIPOC leaders to meet, learn, grow, conspire, relax, feast, and importantly - to be supported, and celebrated.”

The Neighbourhood Group Community Services - Amanda Blands

The Neighbourhood Group Community Services (TNGCS) was thrilled to partner with our sibling organizations on B-I-POC Leadership Energies (BLE). Our sector has been acknowledging the need for more diverse leadership for many years, but is recognizing that representation is simply not enough. BLE created the space to address the challenges that impact leadership advancement for BIPOC women and 2-Spirit, trans and non-binary folks, while creating a peer network and carving a new path forward for leaders in nonprofit spaces – all led by the B-I-POC leaders. This is incredibly exciting work, and it is the kind of work that will move us toward sustainable change. In our organization, our Truth and Reconciliation (T&R) Committee and our Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Committee, comprised of union and management workers, along with their taskforce groups, are at the forefront of this change. At TNGCS we are committed to supporting and empowering the Black, Indigenous and racialized staff in our organization, and to making space for challenging the status-quo which may push us toward new and different leadership models.

Catholic Crosscultural Services - Nadia Afrin and Agnes Thomas

The BIPOC Leadership Energies (BLE) project is a crucial initiative to be part of for CCS, as it aligns with our commitment to diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging. It helps solidify and expand our Anti-oppression work and Leaders In Training Project that began in 2020. Our engagement in BLE led us to establishing a "job shadowing" program within CCS that will build the capacity of BIPOC staff, with a focus on women, trans and nonbinary folks. The job shadowing program aims to retain diverse talent, create pathways for career advancement, and better serve the communities we work with. Through BLE, we are not only investing in the development of our staff but also building a more diverse and inclusive organization that is better equipped to meet the needs of the communities we serve.

Waterfront Neighborhood Centre - Natasha Francis

Waterfront Neighbourhood Centre was so honoured to be a part of the BIPOC Leadership Energies (BLE) project. BLE has widened our opportunity to support our team members that identify as BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary in a focused and specific way. It has also provided WNC with a blueprint on how we can create these spaces for team members to feel that they are being heard and seen.

WNC plans to incorporate the learnings from BLE in our strategic plan and share the learnings with our board of management. We also plan to give opportunities for those who were a part of BLE to share their learnings among our BIPOC women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary team members. BLE signifies the importance of this work and provides WNC with a starting point to continue supporting our members in an impactful way.

Potential Tensions and Challenges in Leadership Energies that did not Emerge in the Data

We are cautious not to romanticize Black, Indigenous, and racialized leaders, recognizing the limits of representation in the ongoing presence of white supremacy. We share the following thoughts with a clarity that these tensions and challenges exist precisely because of white supremacy. As such, we invite white readers to continue to reflect on how the system they benefit most from has created and sustained these dynamics. Furthermore, we invite consideration of the ways in which white supremacy is gendered to protect the perceived well-being and innocence of white women in particular. Heather Laine Talley (2019) speaks to the ways in which white women uphold white supremacy culture, such as a disavowal of power, an obsession with the future, performing anti-racism, overdelivering, niceness above all else, and confusing informality with equity

We will also not share a fulsome examination of tensions and challenges here, as these dialogues need to happen in community, in private, and away from the dangers of the white gaze.

Representation alone will not create transformative change. Increasing representation of Black, Indigenous, and racialized leaders while leaving systems, practices, policies and organizational cultures intact will inevitably result in harmful conditions for these leaders (Shah et al, 2022b). Organizations need to grapple with how institutional silences, priorities, gatekeeping, extraction, exploitation, and inaction have sustained power imbalances as a prerequisite to changing leaders and leadership structures. Being a Black, Indigenous, or racialized leader does not automatically mean that your leadership style or orientation is anti-racist, anti-colonial, and/or anti-oppressive, or that it addresses anti-racism through intersectional orientations (i.e., intersections of white supremacy and cisheteropatriarchy, settler colonialism, ableism, Christian hegemony, capitalism, and more).

Internalized dominance and colonization may lead to forms of lateral harm, in which Black, Indigenous, and racialized leaders direct anger, rage, and harm towards one another instead of directing these emotions towards fighting against systems of oppression. These forms of lateral violence (socio-politically) may also show up in vertical relations between leaders and those who report to them. While we may not agree with all of the points raised in these articles, we consider them important conversation starters in protected spaces for leaders at all levels of an organization to support healing, community, and solidarity.

- https://forgeorganizing.org/article/building-resilient-organizations

- https://drcareyyazeed.com/why-black-women-hurt-each-other-in-the-workplace/

Once again, we want to reiterate that these challenges happen precisely because of white supremacy, a system intended to divide, conquer, and pit people and communities against one another. Racial affinity spaces are imperative for the healing, community-building, and dreaming necessary to create radical alternatives. There are some spaces in which white people are not welcome, and any feelings of temporary exclusion should not supersede the need for racial affinity spaces.

We also want to note the need to examine relational racialization as we make sense of the power asymmetries and dynamics within and between Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities. This requires that we continue to separate B-I-POC, recognizing that the experiences between these groups are vastly different, and recognizing that the experiences within any one of these groups is numerous, complex, and both complementary and contradictory. Possibilities for solidarity need to grapple honestly with the ways in which anti-Blackness and anti-Indigeneity permeate all spaces.

Finally, the work of true solidarity needs to be problematized again and again, challenging the ways in which “allyship” is performed for self-interest, social benefit, or career advancement, or self-declared as a badge of honour. We are drawn to this living text by Elmwood Jimmy and Vanessa Andreotti titled Wanna be an ally? that invites deep self-reflection and possibilities for new forms of co-existence. As such, this work will always be a practice. This work will always be in process. There is no destination or outcome that captures the breadth of possibility.

Possibilities and Cautions of Replicability and Sustainability

We offer the following insights as paradoxes, inviting deeper engagement with the nuances and complexities of the replicability and sustainability of this work.

Possibilities and cautions of replicability: This is an examination of scale. We want more Black, Indigenous, and racialized women, 2 Spirit, trans and non-binary leaders to experience affinity spaces and to have opportunities to imagine leadership differently, while honouring approaches to leading that have not been historically acknowledged by institutions. We also want to challenge conceptions of “scale” rooted in capitalist notions of “growth”, “progress” and critical mass that keep us wanting more, bigger, better (brown, 2017). A hyperfocus on progress, often regarded as an indicator of success, reveals ties to cultures of white supremacy. In always aiming for growth over impact, progress becomes associated with dominance (Okun, 2021). Instead, we might consider how we scale deep (brown, 2017) for radical transformation, to foster more meaningful relations, reflections, actions, and containers of care and experimentation. This requires that we prioritize the alternative, the communal, the local, the periphery.

Possibilities and cautions of sustainability: This is an examination of change over time. We want to create solid structures (financial and other) to support community engagement, creativity, and care. We also want our structures to be nimble and permeable enough to respond to changing communities, ideas, and values. This means that conflicting ideas and values are seen as opportunities for generativity and creativity, and they are welcomed, named, and discussed respectfully. Possibilities and cautions of taking action: This is an examination of the motivation for action. We want to take action to interrupt patterns of oppression that continue to harm historically oppressed populations, communities, staff, and leaders. Transformative action requires an element of risk[1], not an opportunity to parade progressiveness. Sometimes, pausing the desire to “produce” is the most transformative action we can take, allowing ideas to germinate, relations to strengthen, trust to build, and insights to emerge. Sometimes, inaction is a tactic of white supremacy to maintain access to power and protection. Honestly discerning between these approaches to action and inaction is important to transformative work.

Possibilities and cautions of transition in leadership: This is an examination of leadership structures. As we challenge individual hierarchical, simple notions of leadership that promote power-over as opposed to power-with, we might look to examples such as feminist co-leadership to offer fundamentally different orientations. We might also challenge systemic and cultural expectations that Indigenous, Black and racialized leaders “conform” to how things have “always been done” in order to be deemed “professional” or the “right fit”.

Possibilities and cautions of voice: This is an examination of the purpose and power of voice. It is important that Indigenous, Black, and racialized staff and leaders are meaningfully consulted and seen as experts of their own experiences. However, Indigenous, Black, and racialized leaders are often asked to speak on behalf of communities they represent, tokenizing their value and essentializing the diverse experiences of people in those communities. They are also asked or expected to say the unpopular, risky, difficult truths needed to create the discomfort necessary for change, allowing white colleagues to maintain their protection and preserve their reputation.

Possibilities and cautions of partnerships: This is an examination of the place and purpose of partnerships. It is important to challenge patterns of extraction in partnerships with Black, Indigenous and racialized people, communities, and organizations by centering relationality and reciprocity. It is also important to disrupt patterns that aim to partner with staff, leaders, and organizations to appear woke, anti-racist, equitable, or inclusive and engage in true collaboration, co-creation, and knowledge and power sharing.

Possibilities and cautions of dismantling and creating anew: Challenging white supremacy in organizations requires dismantling structures that have historically harmed and created barriers for Black, Indigenous, and racialized leaders. However, dismantling structures requires alternative spaces be created and fostered in order to practice liberatory leadership and center ways of knowing and leading that have been marginalized, such as those in the The UnLeading Project. Simultaneously, creating alternative and liberatory spaces while bypassing the material and political effects of white supremacy will only ensure its continuance.

[1] Black, Indigenous, and racialized people, and women, gender non-binary and trans people, in particular, are regularly negotiating what Rania El Mugammar calls “economies of risk”.

Dreaming Different Rivers

All organizations are systems that inevitably uphold and maintain white supremacy and intersecting systems of oppression. In part, oppression is maintained by having us believe that change is difficult because this is the way it has always been. On the one hand, those working for transformative justice and engaging in everyday practices of transformative justice within systems are continuously reflecting on and working to change themselves, their relations, the structures, and the ideas that undergird their work. On the other hand, they must also reckon with the fact that they are still an instrument of a system that upholds the very structures they are aiming to dismantle and recreate.

Leadership that challenges systems of oppression must be willing and able to dream new relations and ecosystems of change, renewal, liberation, freedom, reflection, questioning, restoration, rest, reclamation, healing, play, pleasure, embodiment, and connection with human and more-than-human worlds. The practice of dreaming invites us to loosen our grips on how it has always been, recognizing that those ways have kept us separate, depleted, overworked, disconnected, afraid, insecure, and partial. This is a gift for us all.

An Invitation

We invite all leaders, at all levels of an organization or community to consider and practice a new liberatory consciousness of leadership. We share the following questions as invitations for practice and reflection:

- What does it mean to lead from and with wholeness, freedom, justice, and thriving? What does it mean to make wholeness, freedom, justice, and thriving possible for others in your organizations, communities, and life? (These questions are inspired by the work of the Liberatory Leadership Partnership.)

- How might it feel in my body to live from places of greater wholeness, freedom, justice, and thriving? How might it feel in our organizations and communities to collectively engage from places of greater wholeness, freedom, justice, and thriving? (These questions are inspired by the work of the Liberatory Leadership Partnership.)

- What becomes possible in dreaming and co-dreaming different futures, different possibilities, and different presents?

- How might we honour models and lessons of leadership from unexpected places and people? This may include lands and waters, the more-than-human, children, ancestors, spirit, crises, depths of despair, intuition, our stories, our bodies, our mothers, our grandmothers, and more.

- How might we practice being in the in-between space of growth, creation, crisis, change, both/and, transformation, complexity, and rupture instead of engaging in fantasies of closure, perfection, innocence, purity, progress, control, and objectivity?

Resources

Please click here for a list of Resources. Continue

Resources

http://culturalstudies.ucsc.edu/PUBS/Inscriptions/vol_3-4/minh-ha.html

Departures in Critical Qualitative Research, 5(3), 55-76.

TNC SIGN IN

LOST PASSWORD

RESET PASSWORD

Password reset link is invalid or expired.

Please request another password reset email.

To request another reset password link click here

Setup Admin Account

Admin Account setup link is invalid or expired.

RESET PASSWORD

Setup Admin Account

Success

Page has been updated successfully.

Failed

Page has not been updated.